Opening – Still the Question That Starts Fights

If I had a dollar for every time a customer asked me, “Should we go hot runner or cold runner?” I could probably retire early. And honestly? That question still starts debates between engineers, buyers, and plant managers as if it’s some deep philosophical riddle. I’ve been knee-deep in injection molding since before USB-C was a thing, and I can tell you—this choice isn’t about picking the “better” system. It’s about matching the right tool to the job, your volume, your wallet, and your tolerance for occasional headaches. Let me walk you through it the way I explain it on the shop floor: with stories, cautions, and a few laughs along the way.

First, Let’s Get on the Same Page

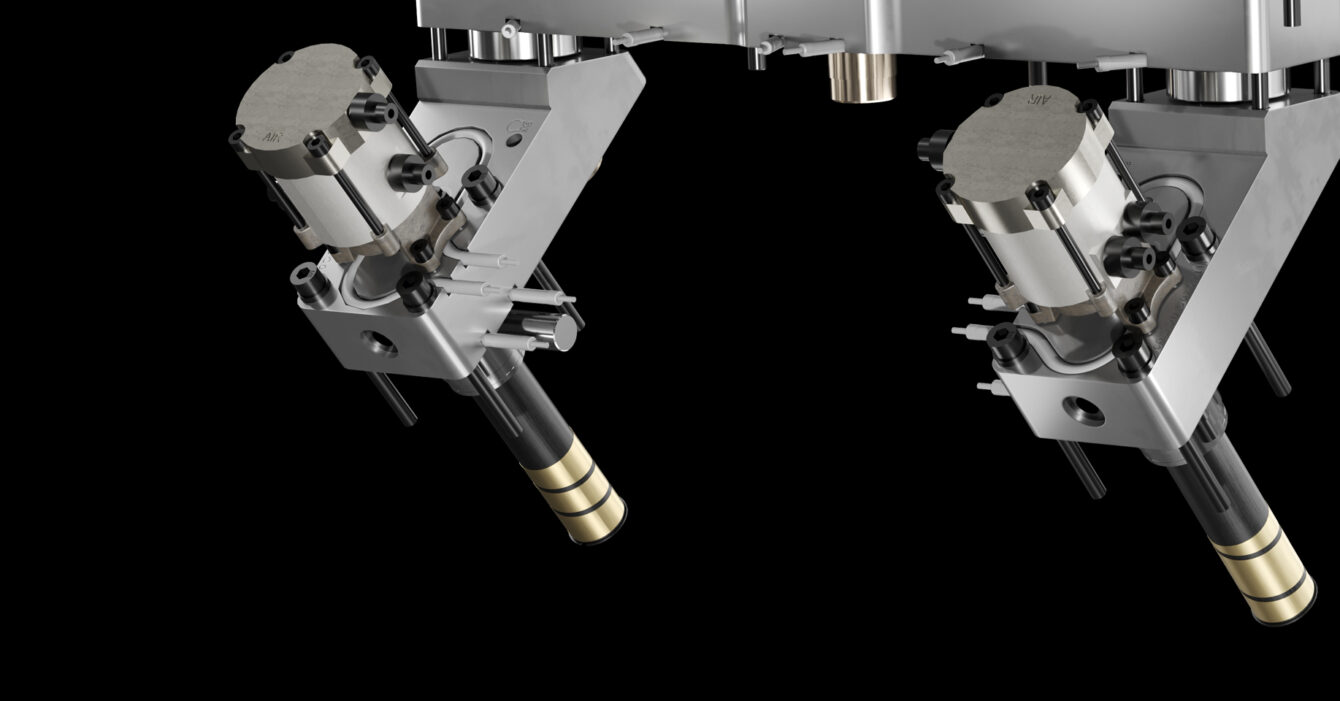

Cold runner is the old faithful: plastic travels through a sprue and solid runners into the cavity. After the shot, you open the mold and physically remove the runner—snip it, break it, whatever fits your workflow. Simple, cheap to build, but you toss plastic every cycle. Hot runner keeps the plastic molten in heated channels and nozzles, so it flows straight into the cavity. No solid runner to discard, less material waste, and potentially faster cycles. But you pay more upfront, and you’ve got heaters, manifolds, and controllers to babysit.

Cold Runner – Where It Shines (and Where It Bites)

When I Reach for Cold Runner

- Prototypes or low-volume runs — say, a few hundred to 10k parts. You want cheap and quick turnaround.

- Materials that are inexpensive or easy to recycle — PP, PE, sometimes PS.

- Parts where gate vestige doesn’t matter — hidden gates, non-cosmetic surfaces.

- Simple geometries — fewer headaches aligning multiple drops.

I remember a startup that needed a two-cavity mold for a simple polypropylene container lid. Budget was tight, timeline brutal. We went cold runner, cranked out parts in days, and they were happy. But six months later, they wanted to scale to 50k/year. Suddenly, that manual trimming became a production bottleneck and a quality control mess. Lesson? Cold runner is great until volume turns it into a labor sink.

The Trade-Offs

- Runner scrap adds cost over time.

- Trim labor can eat into profits.

- Gate location limits cosmetic options—you can’t always hide the mark.

- Cycle-wise, you lose a bit because you wait for solidification of the entire runner system before opening.

Hot Runner – When It’s Worth the Extra Headache

When I Push for Hot Runner

- High-volume production — 50k shots and up, especially if you’re talking hundreds of thousands or millions.

- Engineering plastics — PC, POM, Nylon, etc., where material cost is high and scrap hurts.

- Cosmetic parts — no visible gate vestige, smoother surfaces.

- Multi-cavity or family molds — precise control over flow balance.

I once worked on a six-cavity hot runner mold for automotive bezels in ABS. Client was obsessed with eliminating gate witness lines. With a well-tuned hot runner, we nailed consistent fill, zero trimming, and a cycle almost 6 seconds faster than the cold runner version they tested. Material savings alone paid back the extra mold cost in under a year. But—here’s the kicker—the first month was hell. Thermocouple drift, heater band failure, and one nozzle that kept drooling plastic until we replaced the tip. Hot runner means you must maintain it like a race car engine.

Trade-Offs

- Higher initial investment — manifold, heaters, controls.

- More complex setup — temperature zones, tuning, leak checks.

- Maintenance-sensitive — a failed zone can ruin a whole batch.

- Not ideal for short runs — ROI takes time.

Hot Runner Brands I’ve Used (and What I Learned)

Over the years, I’ve installed and fought with just about every major hot runner brand out there—some I loved, some I tolerated, and some I’d rather forget. Here’s the honest rundown from my bench:

1. Husky (Now part of PSG, but still Husky in spirit)

- Where I see it: Large automotive and packaging molds, high-cavitation systems.

- Pros: Rock-solid construction, excellent temperature control, great support if you’re in their “big customer” tier. Valve gate precision is top-notch.

- Cons: Pricey—sometimes shockingly so. Lead times can be long if you’re not a priority account. Spare parts… let’s just say you learn to stock them.

- My take: If you’re doing million-shot runs and need bulletproof reliability, Husky’s worth every penny. But for a small custom injection mold? Might be overkill.

2. YUDO (South Korea)

- Where I see it: Mid-range multi-cavity molds, electronics, medical.

- Pros: Good balance of performance and cost. Decent valve gate systems, reasonable lead times, and their tech support in Asia is responsive.

- Cons: Temperature stability not quite Husky-level; I’ve seen minor drool issues if tuning isn’t spot-on.

- My take: Sweet spot for many mid-volume jobs. Reliable if you do your homework on setup.

3. Mold-Masters (Canada, now part of Barnes Group)

- Where I see it: Complex multi-material and high-cavitation molds worldwide.

- Pros: Innovative designs, excellent for sequential valve gating, very good melt control. Their hot half systems are modular—easy to modify.

- Cons: Can be expensive, and documentation sometimes assumes you’re already an expert.

- My take: Great for tricky parts where you need precise gate timing. Support is decent if you’re used to their ecosystem.

4. INCOE (USA)

- Where I see it: Industrial and large-part molds, often in North America.

- Pros: Strong legacy in large systems, robust nozzles, wide range of accessories.

- Cons: Older controller interfaces feel dated; training new techs can take extra time.

- My take: If you’re running big, thick-walled parts in hot runner, INCOE holds up well. Just budget extra time for setup.

5. Chinese brands (e.g., Sino, Anole, Hasco China versions)

- Where I see it: Cost-sensitive projects, prototypes, growing domestic market.

- Pros: Much lower upfront cost, faster delivery, improving quality rapidly. Local support is quick and cheap.

- Cons: Temperature uniformity and longevity can’t match top-tier Western/Korean brands yet. You need to be careful with heater bands and thermocouples.

- My take: Perfect for low-to-mid volume or when budget’s tight. I’ve used them successfully on custom injection molds for indoor appliances—just plan for more frequent checks.

What I Look for When Picking a Brand

- Application fit: High-precision valve gating? Go Husky/Mold-Masters. Simple open nozzle? Maybe YUDO or a solid Chinese brand.

- Support & parts availability: I’d rather pay a bit more for a system whose spare parts I can get in 48 hours.

- Team familiarity: If my crew knows a system inside out, that’s a huge hidden advantage—training time drops, mistakes drop.

- Total cost of ownership: Cheaper upfront can mean pricier headaches later.

Real-World Decision Factors (From My Bench)

Volume & Economics

I always ask: “How many parts, and how long will we run them?” If it’s a bridge tool for market testing, cold runner wins. If it’s a mainline product for years, hot runner often pays off. Run the math: factor in material cost × scrap rate, plus trim labor, plus cycle time. Sometimes the numbers surprise you.

Material Type

Cheap resins? Cold runner’s fine. High-cost or sensitive ones (like clear PC or glass-filled PA)? Hot runner reduces waste and avoids regrind issues.

Part Cosmetic Requirements

If customers won’t tolerate any gate mark, hot runner (or valve gate hot runner) is usually the only way.

Mold Complexity

Balancing multiple cavities in cold runner is tricky—you might get overpack in one cavity and short shot in another. Hot runner gives finer control.

Stories from the Trenches

- Cold runner fail: A client insisted on cold runner for a 100k-run medical part. We warned about trim labor, they ignored us. Six months in, they hired three extra people just to snip runners. Cost overrun bigger than the mold savings.

- Hot runner win: Another client switched from cold to hot runner on a high-gloss ABS panel. Scrap dropped 95%, and they eliminated a secondary finishing step. Sales team bragged about “zero-defect appearance.”

- Hot runner headache: Had a nozzle heater burn out mid-shift. Machine dumped molten plastic everywhere. We fixed it, but that hour of downtime stung. Moral? Have spares and trained techs.

My Rule of Thumb for Custom Injection Molds

If you’re unsure, start by asking:

1.Volume — low (<10k) → lean toward cold; high (>50k) → evaluate hot.

2.Material cost — expensive or critical → hot runner often safer.

3.Cosmetics — visible gate unacceptable → hot runner.

4.Labor situation — if labor’s cheap and trimming’s easy, cold runner can work; if labor’s expensive or scarce, hot runner helps.

And never decide based purely on mold price. Look at total cost of ownership. I’ve seen clients save 10k on mold,then spend 30k extra in scrap and labor within a year.

Wrap-Up – Match the Tool to the Job

At the end of the day, hot runner vs. cold runner isn’t religion—it’s engineering. Both have their place. Cold runner is simple, affordable, and forgiving for small jobs. Hot runner is powerful, precise, and efficient for serious volume—if you’re ready to manage its complexity. I always tell folks: pick the system that lets you sleep at night. If you’re constantly fighting temperature drifts or trimming bottlenecks, something’s wrong.

Need help sizing it for your custom injection mold? Tell me your part size, material, and expected volume—I’ll give you my gut call, no sales pitch.

(P.S. Got a tricky multi-cavity layout? I’ve got a “Flow Balance Checklist” from my days tuning eight-nozzle hot runners—happy to share.)